Growing up in a rural community near the Texas/Mexico border, Carrie Byington, M.D., understands what it means to live in a medically underserved community. And as she watched COVID-19 overwhelm conventional medical and public health responses and overtake communities lacking ready access to medical care and health resources, it became clear to her: Data would be key to finding solutions for treatment and prevention–and saving lives, especially for those who were likely to bear the highest burden of the pandemic due to health inequities.

Byington is executive vice president of University of California Health, and she knew from her years of research and practice in the fields of infectious disease and pediatrics that the University of California—the nation’s largest public academic health care system—was uniquely positioned to inform effective response and preventive action. The University’s clinical sites had data from real-world work with patients, as well as world-class investigators experienced in health science research.

But these data never had been used before to drive a rapid, evidence-based response to a new infectious disease. Byington was quick to call for action, initiating the creation of a data set through UC Biomedical Research Acceleration, Integration & Development (UC BRAID)—which is a consortium of the Clinical and Translational Science Awards programs at UC Davis, UCI, UCLA, UC San Diego and UCSF—and UCH’s Center for Data-driven Insights and Innovation (CDI2).

In a matter of weeks, the resulting effort by a multi-site analytics team of 30 people established the University of California COVID Research Data Set (UC CORDS), one of the nation’s first COVID-19-focused sets of real-time data from patient encounters.

UC CORDS gathers de-identified data points in a HIPAA-compliant limited data set from patient electronic health records (EHRs) from across the five main academic health centers that UC operates.

Breaking down disparities

UC CORDS has been the basis for insights crucial to fighting the virus as well as understanding the risk and outcomes of illness for diverse populations. Jonathan Watanabe, Pharm.D., Ph.D., associate dean of Pharmacy Assessment and Quality, School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, and professor of Clinical Pharmacy at UC Irvine, first identified trends in age, comorbidities, and hospitalization for COVID-19. Yong Huang, a computer scientist and Ph.D. student at UC Irvine’s HealthSciTech Lab, produced a groundbreaking view of “long COVID” highlighting a greater risk for women to develop “long-haul” syndrome; other UC researchers have investigated gender and PCR test sensitivity, racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 illness among patients with preexisting dermatological conditions, and more.

Miriam Nuño, Ph.D., a public health researcher and trained statistician at UC Davis, saw an urgent need to understand even more than race and illness. “My work is to try to understand disparities from every angle,” she says. “That means investigating details that put a face on at-risk populations.”

Working with UC CORDS, Dr. Nuño not only confirmed that males, older people, patients with multiple pre-existing comorbidities and people identifying as Hispanic/Latino were at greater risk for hospitalization and death; she also discovered a degree of risk to Asian populations that had gone undetected. Attributing the size of UC CORDS database with making her findings possible, Dr. Nuño adds, “Academic medicine is not just looking into the future—it’s also about what’s happening right now, in the moment.” She saw that work with the type of nearly real-time data available in UC CORDS would enable investigators like her to provide information that helps public health entities, policymakers and citizens make decisions and take action.

Accelerating insights

In just two years, 16 peer-reviewed publications and pre-prints have already been produced by researchers at five UC campuses including UC Davis, UC Irvine, UCLA, UC San Diego and UCSF. It’s a remarkable milestone given the typically lengthy timeframe for medical research from investigation to publication. UC CORDS, which launched with 460 million data points, keeps evolving. More than 200 UC researchers from across all of UC’s health locations continue to work with a current set of 640 million data points to investigate the disease in the context of age, pre-existing conditions, health equity indicators, and more.

The impact of UC CORDS, says Byington, is doubly rewarding. “UC’s academic health centers are privileged to serve California’s diverse communities. Making this type of data immediately available to researchers is paving the way for informed decision-making about effective treatment one patient at a time and cumulatively, to help eliminate disparities in care for populations at risk.”

Atul Butte, M.D., Ph.D., is University of California Health’s chief data scientist and head of CDI2 and adds, “When physicians have access to statistically significant insights from clinical practice as well as medical research, they’re better equipped to make the most effective therapeutic recommendations to their patients.”

Given the large, diverse population represented by UC CORDS, the data set has informed public policy and public health guidance at the state and national level. Early in the pandemic, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sought insights from UC CORDS to understand the spread of COVID-19 and the uptake and effectiveness of emergency-authorized therapies and vaccines, as well as to inform public guidance in response to the disease.

A living research tool

The team that built UC CORDS had to solve for unprecedented requirements and unforeseen challenges—and in doing so, created a research tool that continually evolves with the virus and the pandemic. The data set is refreshed monthly and the effort to ensure its relevance to users is one that’s ongoing. It may also serve as a model for using diverse, real-world data sets to rapidly address health challenges in the future.

Rohit Vashisht, Ph.D., a clinical data scientist in the Butte Lab at Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute at UCSF, says that at the outset of the pandemic, data circulating in the public domain was limited to COVID-19 positive or negative test outcomes.

The source for UC CORDS was much richer: the UC Health Data Warehouse, which contains clinical data collected during routine care in EHRs that also include information about demographics and pre-existing conditions for hospitalized patients as well as outpatients. To build UC CORDS, the analytics team consulted with end-users—clinicians and researchers—to determine what they needed to access related to clinical aspects of COVID-19 disease progression and to ensure the use of standardized terminology. Ayan Patel, M.S., lead data scientist, CDI2, says, “Until COVID-19, ventilator-specific data were used infrequently, but now we had to have a standard way to reference them in health records.”

Standardizing the data was just the first step. Vashisht has been responsible for the interfaces and dashboards that make UC CORDS usable for medical researchers—not just computer and data scientists. He has worked to ensure the quality of the UC CORDS database based on acceptable community standards as well as developing computational programs and tools to query UC CORDS for insights sought by CDPH and FDA on a near-daily basis.

“Researchers using the de-identified data points in UC CORDS could know, for example, whether admitted COVID-19 patients were more likely to have pre-existing conditions such as diabetes or asthma,” says Vashisht. “Then we could begin to investigate whether these patients might be at greater risk for hospitalization based on these pre-existing conditions, what medications they were taking, how they fared, if they were hospitalized, and so on.” Vashisht and team were the first to use real-world data from UC CORDS to generate insights on underlying sex- and age-related differences in the time to develop an antibody response to COVID-19 infection.

Watanabe, who produced the first documentation of trends in clinical treatment practices and an analysis of medication use for both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients based on age and baseline chronic conditions, has his own perspective on the content of UC CORDS—in particular, the geographic breadth of patient data and the implications for equity in access to care and treatment.

“When there really wasn’t a playbook for COVID-19 treatment, I wanted to find out what clinicians were doing and how that was shaped by evidence trickling out about what did or didn’t work,” says Watanabe.

“UC CORDS made it possible to find out almost in real time what was happening in practice, and in a set of clinics that together serve an incredibly diverse range of patients, including the state’s most vulnerable populations who suffer from a higher incidence of chronic disease and negative outcomes. I’m immensely appreciative of the local support provided for this work by the UC Irvine Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences,” Watanabe added.

The starting point for trailblazers

It’s easy to imagine research and data scientists working at their own pace in spotless computer labs. But the reality of UC CORDS-based research is something different, undertaken by primary investigators who have had colleagues and friends touched by the disease, and clinicians providing care despite the uncertainties of treating a novel virus.

Amir M. Rahmani, Ph.D., M.Sc., associate professor of Nursing and Computer Science at UC Irvine, also leads a multidisciplinary team of researchers in UC Irvine’s HealthSciTech Group and is one of the data scientists urging the use of UC CORDS since inception. Rahmani’s motivation? The experience of a fellow primary investigator who contracted COVID-19 early in the pandemic and her struggle to find help for lingering symptoms.

Rahmani and members of the UCI Institute for Future Health studied the course of COVID from contraction through development of symptoms and antibodies, by gender, before any other researchers reported on this information. One benefit of the research: the elimination of premature antibody testing following a positive COVID-19 result.

Rahmani and team also were able to establish a way to distinguish COVID-19 from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a condition with similar symptoms, using just basic heart rate and blood pressure data.

Yong Huang, the student researcher who reported predictors for long COVID, is especially interested in advancing the disease’s phenotype, or characteristics and traits. Huang produced one of the first detailed accounts of symptoms by disease variant. He says, “Because UC CORDS includes inpatient and outpatient records, I had the opportunity to look at the entire spectrum of patients, from those who have mild or no symptoms to those with severe illness. Other public data sets only held records from hospitalization,” and would have limited Huang’s efforts to characterize COVID-19.

Impacts beyond COVID-19

Two years since the creation of UC CORDS, the data scientists and analytics teams executing the UC CORDS initiative see implications for the future of medicine and health care, as well. Lisa Dahm, Ph.D., CDI2’s director, health data and analytics, recognizes a need and opportunity for hybrid expertise and for data scientists to apply their training to requests from medical practitioners, to gain an understanding of how to work with health care data.

"The work with the UC CORDS data set is a very tangible example of how we as an academic health institution are translating bench research into bedside care. Data research and modeling has become a critical part of advancing the practice of medicine. The practices developed using UC CORDS will be a meaningful model for data-driven investigations going forward," added Dan Cooper, M.D., who served as chair of UC BRAID when UC CORDS was launched.

Researchers using UC CORDS are just as committed to finding an end to COVID-19 and to better managing the disease as a matter of public and individual patient health, in the meantime. Rahmani’s team holds weekly brainstorms to surface new research topics such as gender differences in vaccination rates and impacts. Vashisht is evaluating data from the National Institutes of Health’s National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Data Enclave of more than 15 million individuals tested for COVID-19, to determine whether findings from UC CORDS effectively represent trends at a national level; if confirmed, the utility of the data set will extend beyond the state to support national efforts to treat COVID-19.

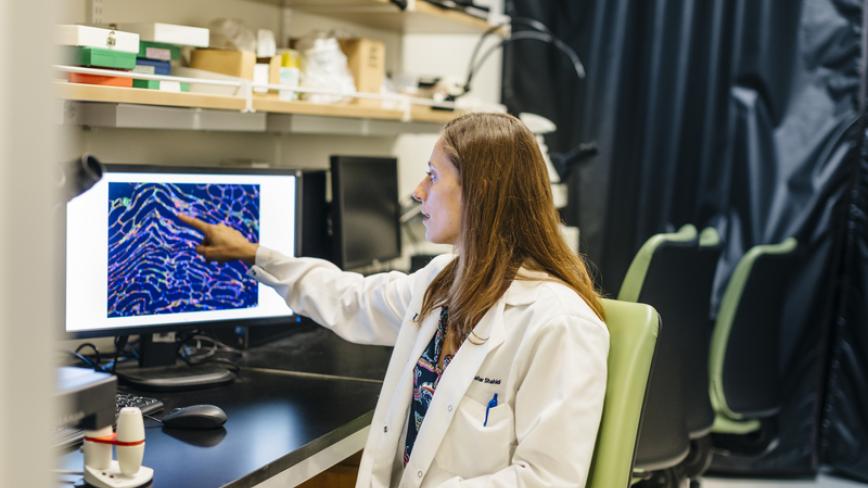

The effort put into UC CORDS has benefited patients, and not just indirectly. Natasha Mesinkovska, M.D., Ph.D., and fellow researchers and physicians were instrumental not only in determining what to include in the data set, but also what urgent patient concerns to investigate.

A practicing dermatologist at UCI, Mesinkovska explains: “Atopic dermatitis is a condition commonly associated with respiratory issues, as a result of inflammation triggered by immune response. So we needed to know whether these patients were getting sick with COVID-19, and how best to help them.”

To Mesinkovska’s relief, her team’s review of UC CORDS data did not show atopic dermatitis patients were at greater risk of becoming ill with the virus. As for alopecia sufferers, Mesinkovska was able to advise the National Alopecia Areata Foundation that their autoimmune condition did not appear to put patients at greater risk of COVID-19, either.

Like Dahm, Mesinkovska sees the opportunity for hybrid skills. In the early days of UC CORDS’ construction, she says some of the doctors on her team had to learn to code, adding “It was a beautiful thing to see our dermatologists and bioinformatics teams working together. It made us better doctors–and hopefully our patients are grateful for it.”